Statistical Anthropometrics

Francis Galton is today remembered as an eminent prince of science if not also as a wild crank who, at the end of the 19th century, helped spawn the grandiose political disaster of eugenics, the ripples of which would continue to be felt far into the 20th century. Less discussed is how all Galton’s projects, from his scientific contributions to statistics to his politics of eugenics, depended on technologies of measure.

Among these technologies devised by Galton’s intellect as the concept of percentile ranking (he called them ‘centiles’). Today it is routine for us to ask which percentile we fall into among a population measured on a standard scale (such as a SAT, ACT, LSAT, or GPA score). These percentile rankings mean something to us almost automatically. Simple as the idea is, it is easy to forget that somebody had to come up with this method of classing scores. Galton himself said of his work on the concept: ‘All this is an old tale now, but I had to take a great deal of trouble before it was clearly thought out and well tested’ (1908, 268).

Consider another technology employed and improved by Galton. The core technological apparatus for formatting, or the structuring of data, found throughout Galton’s researches is the deceptively simple printed blank form: a sheet of paper with rules and lines, a handful of pre-printed words describing categories, and a set of clearly defined blank areas which one is meant to fill out.

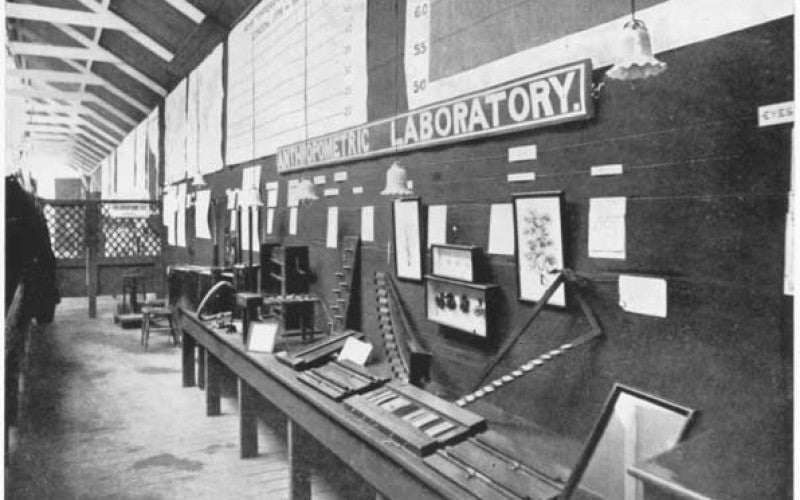

One paradigmatic deployment of Galton’s forms were in his anthropometic labs. The first such lab was set up at London’s International Health Exhibit in South Kensington in 1884 where attendees paying threepence could walk through the laboratory, a 6-foot by 36-foot “long narrow enclosure,” to take a series of tests measuring such powers as eyesight, reaction time, span of arms, force of blow, and so on (Galton 1908, 245). The seemingly simple idea of giving a person a series of tests of bodily and perceptual ability assumed a new meaning once experts, scientists, and cranks of all kinds began recording those results on standardized printed forms. Galton reported that at the Health Exhibition alone “the number of persons measured in the laboratory . . . was no less than 9,337, and each of them in 17 different ways” (1885, 206). Each of them left with their own copy of the just produced record of themselves as recorded on a printed blank form.

Galton kept all the records produced at the exhibit, and they informed his interest in heredity as the foundation of distinctions between persons. He cultivated a branch of hereditarianism that ventured if we cannot nurture the individual, perhaps we can nurture nature. Thus was conceived eugenics – good breeding for heritable traits. Galton hoped for his project of eugenics to be nothing short of a scientific implementation of racism. But the program never grew to the dimensions he had hoped. The legacy remnants of his odious hopes and tinkerer innovations might be excavated today less by way of the attitudes of individual contemporary data scientists implementing his statistical techniques and more in how data technologies themselves function as a crucial component of the structural maintenance of inequalities of race.

The blank form was further solidified as a key technology in his construction of an analytical science of the data of heredity through his publishing in 1884 of Record of Family Faculties, Consisting of Tabular Forms and Directions for Entering Data with an Explanatory Preface. The book is essentially a data collection machine consisting of some 50 pages of printed blank forms on which a form-filler would write the names of their ancestors (Galton 1884, 14), then children (Galton 1884, 15), and then describe in detail each of the known family members in terms of vital information (birthdate, birthplace), bodily measures (height, hair color, “general appearance”), mental measures (“mental powers and energy”, eyesight), notes on “character and temperament,” and finally medical information regarding ailments, major illnesses, and causes of death (Galton1884, 16–60). It was a book of printed blanks in which one would give an account of something presumed important about oneself. It was a series of predefined boxes into which one fit oneself, one’s spouse, one’s children, and one’s parents.

Galton’s attention to the form demonstrates an awareness of a series of technical operations which many data scientists today routinely neglect—namely, apparatuses for the collection and normalization of those data that algorithms will later be able to process. Galton’s long-form printed blanks are formatting technologies, and they are conceptual infrastructures upon which contemporary informational storage and processing rely. This fact paired with how, as shown in his hereditarianism, they are technologies formatted to produce and reproduce inequalities, raises questions about our complex inheritances of Galton and invites inquiry into how inequalities can be both generated and reproduced through the very formatting of data. For an egalitarian counter contemporary to Galton see the Our Data, Our Selves page on W.E.B. Du Bois's egalitarian data technology.