Racial Informatics & Redlining

In 1951 the American Institute of Real Estate Appraisers (AIREA) published a half-manual-half- textbook titled The Appraisal of Real Estate. The first item in the book’s list of “factors that contribute to the destruction of value,” is “when a new class of people of different race, color, nationality, and culture moves into a neighborhood” (AIREA 1951, 102-3). This statement betrays an accounting technology that had consolidated by midcentury according to which the racial composition of neighborhoods is a calculable factor in the appraisal of market values of residential properties. But behind the matter-of-fact tone and the epistemic authority of such half-manual-half-textbooks is the historical fact that the above statement would not have been possible without a whole flotilla of efforts toward the development of appraisal techniques by private industry in the 1920s.

While attitudinal-ideational racism is odiously present in the historical materials used to make the above argument, there are also deeper structural-institutional forces of racism at play. What can be called “the informatics of race”—or the extension of data to previously dataless concepts of race—was leveraged in the early-twentieth century to systemic levels such that racisms were built into obdurate technologies of appraisal and valuation. This is not only a problem for the past, but it remains a problematic for the present if it is the case technologies that bake racism into structuring social practices outlive the attitudes of their inventors. In short, the disappearance of overt racist attitudes is no guarantee for the disappearance of persisting technological structures (see Bonilla-Silva 2014 on attitudinal and structural racism).

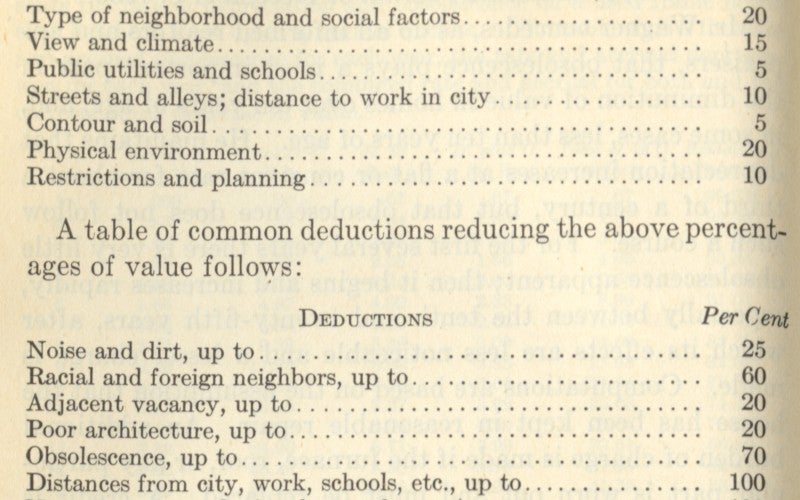

A key early moment in creating a new kind of space for racialization within real estate appraisal was from 1923 to 1925 when the earliest formulations of race-conscious residential property valuations appeared in a range of treatises, textbooks, and articles in professional journals all linked with the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB). By the 1920s, NAREB (founded in 1908) became the national organ for the professionalization of real estate and, in this capacity, it steered the industry toward scientization. One way NAREB did this was to make appraisal an algorithmic science which might be taken up uniformly by professionals across institutional settings such as mortgage lenders, real estate offices, and prospective buyers. The texts and articles NAREB endorsed, and which came to have the greatest influence on the development of real estate in the United States, consistently outlined algorithmic techniques of factoring race into price. One result: to be a professional in the industry was to include race in one’s appraisal equation.

If race became an industry standard factor in residential property appraisal in the 1920s, a later period from 1931 to 1937 was a time of consolidation and systematization. This period was witness to standardizations that could be performed with prefabricated equipment geared to appraisal professionals: standard printed blank forms, standard filing systems, and technical manuals specifying how to use these technologies to maximal advantage. Race was formatted into all these technologies. Race became informationalized. Racial datafication.

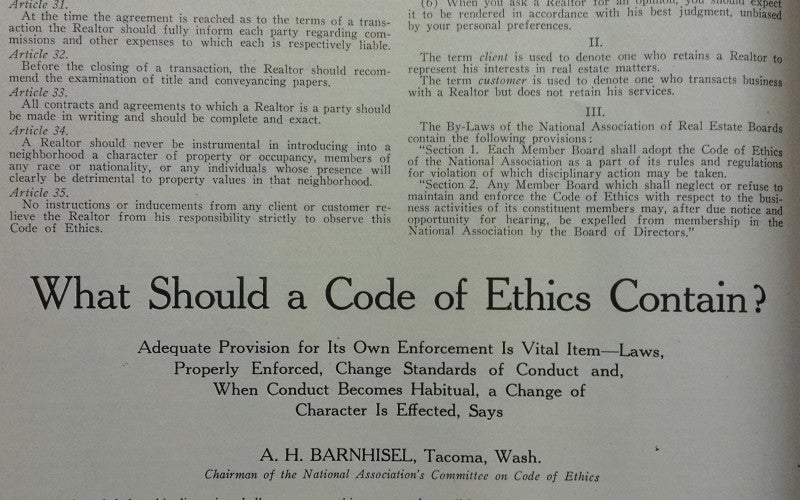

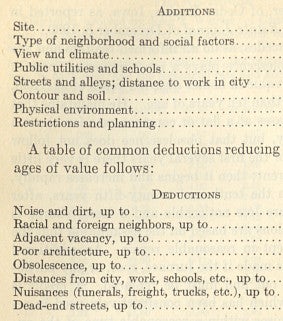

One of the most influential manuals of this period was McMichael’s Appraising Manual, published in 1931 by Prentice-Hall (a second edition was issued in 1937). The manual recommendations equipment for professional appraisers such as cameras, a compass, tape measure, and multiple forms, and it includes a section which reprinted NAREB’s 1929 codes of ethics concerning appraisal practices. The manual also extends the profession’s earlier work and commitments to the racialization of appraisal.

In Chapter 28 McMichael advises appraisers to answer some thirty questions. Two of them, printed one right after the other, are as follows: “Are there undesirable racial elements in the neighborhood, and, if so, are they likely to expand in a way that may injure the property? Are there other undesirable factors, such as odors from stockyards, smoke from factories, odors from swamps, overflows from watercourses, undue noise from passing trucks, exhaust fumes from great numbers of automobiles, etc., etc., which may reflect on future use and value?” (1931, 278).The combination of these two questions is jarring. However, difficult to notice if we attend only to the attitudinal racism we would expect (“undesirable” as attributed to race alongside swamp odors and traffic exhaust) is the simple injunction to factor racial elements into the appraisal. McMichael’s manual offered its reader a kind of code for the measure of worth. The appraiser who answered each question on the list would have followed the procedure to the scientific answer. This, precisely, is how race was factored into valuation as one of many elements in an algorithm.

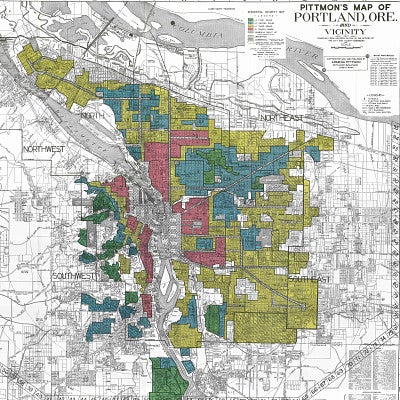

The racializing algorithms codified and disseminated by NAREB would become deeply entrenched in key federal institutions of federal housing policy including the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). When these agencies were created, they did not need to invent new appraisal methods. The uptake of prior appraisal practices was easily facilitated by the fact that many of the same people who had crafted appraisal standards for private industry became appraisal officials at these agencies. For example, Frederick Morrisn Babcock developed appraisal programs for the profession in the 1920s (see Babcock 1924) and then became chief underwriter at the FHA in the 1930s.

By building race into its appraisals, the FHA and HOLC came to have a profound effect on racial inequalities in homeownership. The HOLC assumed about one million loans in a few short years in the mid-1930s. The FHA by contrast was not itself in the business of lending or of taking over defaulted mortgages. Rather, the FHA insured the long-term mortgage loans made by private lenders. To qualify for this insurance, loans had to meet certain conditions. The FHA’s terms for loans extended the life of loans (for up to thirty years), decreased the size of down payments (to less than 10 percent), and lowered interest rates (by two percentage points). An FHA-backed loan was for these and other reasons essentially a government-paid subsidy to qualifying homebuyers. FHA’s appraisal standards were pushed out into the private lending market in that the promise of FHA guarantees gave mortgage lenders a huge incentive to seek loans that met their standards. FHA practices thus became nearly ubiquitous. They were not universal; but they were certainly universalizable throughout the home finance market. As standards, this is exactly what they were meant to be.

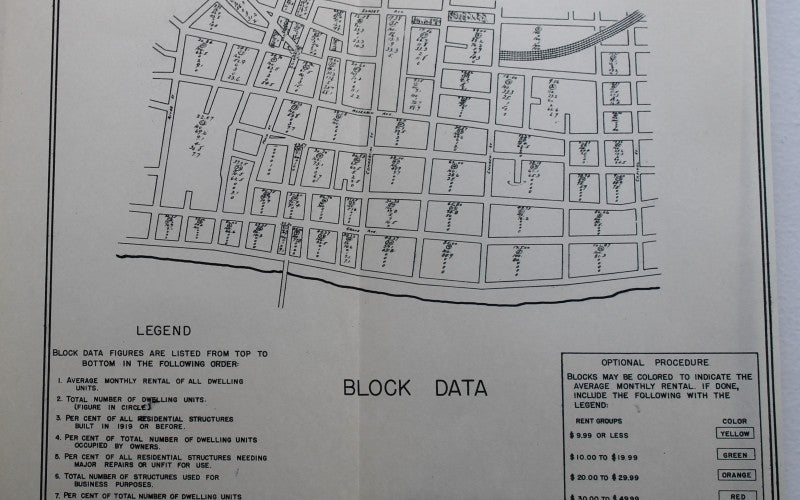

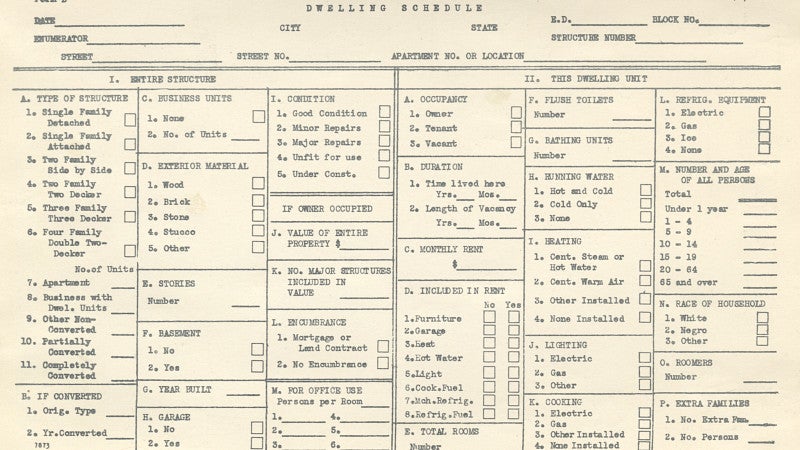

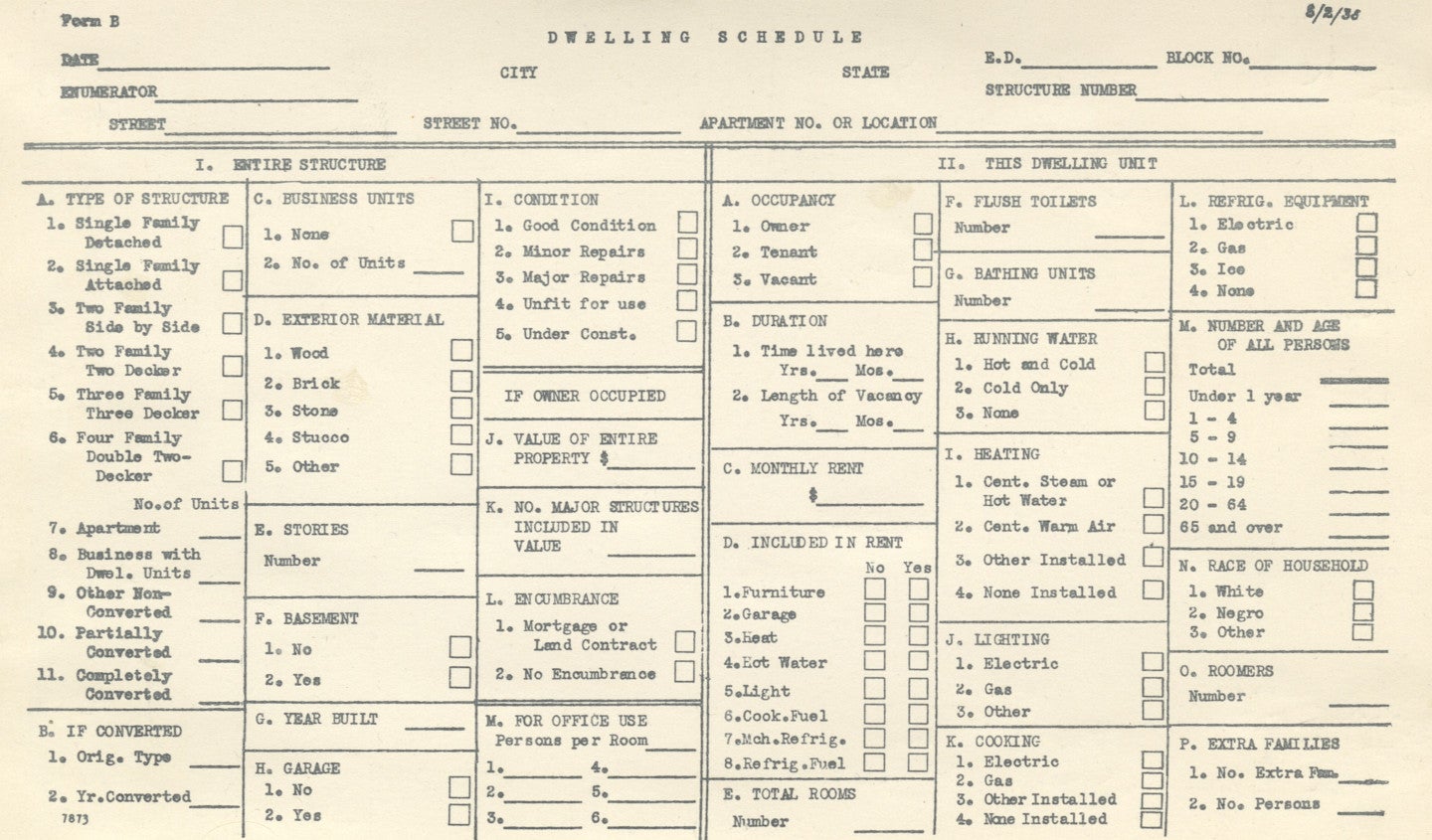

Evidence the FHA deployed appraisal practices that explicitly factored race into market values for residential properties can be found in documents such as a manual produced by the FHA in a joint project with the Works Progress Administration: the 1935 Technique for a Real Property Survey (TRPS). According to the FHA’s Second Annual Report on agency activities, the goal of the TRPS was “a standard procedure for conducting comprehensive real property surveys” (see FHA 1936). In short, the survey was intended to produce a mass of “raw” property data that could later become a basis for appraisal reports, redline maps, and other valuable data sets. Some of those data were collected via the TRPS “Dwelling Schedule” that enumerators would take door to door for data collection.

Box N of the “Dwelling Schedule” was a site for the informationalization of race. At the doorstep, after a short greeting and conversation, what was in one moment the visibility of race—phenotypical appearance—became in the very next moment an informatics of race—a tick in box N according to a protocol: “N. Race of Household: 1. White, 2. Negro, 3. Other.” In this case the protocol was: “Mark in the appropriate box the race of the household, whether white, negro, or other. If any member of the household, other than servant, is negro or of a race other than white, consider the whole household as belonging to that race” (FHA/WPA 1935, §7, 38).

An entire politics of race is contained in such a format. Every dwelling accounted and racialized. A whole series of efficiencies is already coded into the data these forms were able to collect. People’s lives were shaped by algorithms and institutional policies that were built downstream from this data collection. The people recorded on these forms were constituted as data by specific formats, and not others. They were accounted for by their race (but not occupation or education); their race was accounted for singularly (and without mixed-race categorization); their household’s race was accounted for by a real-estate equivalent of the one-drop rule (and in a way that overcodes nonwhite races). In all of this is an entire apparatus of fastening, one result of which was the enactment of mass-scale racially inegalitarian subsidies with a rapidity (fastening’s acceleration) and demobilizing effect (fastening’s pinning) of which no racist ideologue of the preceding decades had bothered to dream up.