Personality Datafication

In 1936 psychologist Gordon Allport, the first major technician of human personality, published a list of 17,953 personality trait terms (Allport and Odbert 1936). Researchers ever since have been working hard to pare down that list into something more manageable. A dominant contemporary approach conceptualizes personality in terms of five core traits (openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). Regardless of how many personality traits we have, or others take us to have, almost all of us tend to think of our personality traits as somehow ineluctably us. In part due to the scientific legacy of Allport and his cohort, we now comfortably recognize ourselves in the apparatus of concise two-dimensional personality profiles on which we can be plotted or charted according to our answers to a finely tuned barrage of questions.

The science of personality psychology that produces these profiles relies on a technical apparatus of questionnaires, algorithms, and graphs that make it an eminently informational science. While few of us treat our personality traits with scientific rigor, even the most casual of trait ascriptions relies on planks of informational assessment put into operation by personality psychology in the first decades of the twentieth century. How did the trait categories and schemas that we take for granted come to be the core elements of both personality psychology and understandings of ourselves?

According to historian Warren Susman, a significant shift in American culture occurred at the turn of the twentieth century when conceptions of personhood cast in terms of character began to be increasingly replaced by ideas of personality (1984, 276). This displacement involved a whole series of transitions, two of which stand out. First, there was a shift from holistic conceptions of character to a notion of personality as a composite always in need of unifying refinement. A second shift had to do with personality being amenable to quantitative empirical scrutiny in a way that character is not—or at least not as readily. This involved a shift from a normative notion of character to a purely descriptive notion of personality. Character was something that one either did or did not have, and it was typically a good thing to have it. But everyone has personalities, and they assume different shapes in different persons such that those differences can be descriptively interrogated.

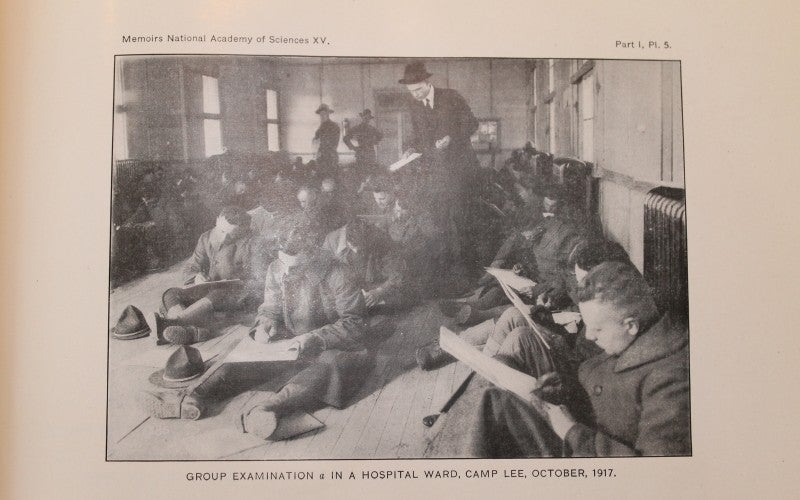

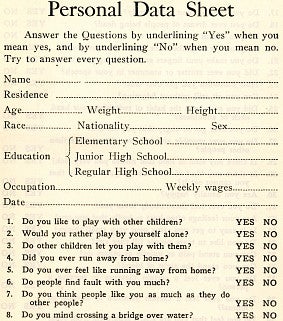

Quantifying measure was an important imperative for early personality psychology. The first truly massive employments of personality measures were developed in the 1900s and 1910s in the work of intelligence testing. Exemplary tests of the time included American military efforts during World War I like the Army Alpha and Beta Tests. Following on from the perceived successes, and quick institutionalization, of early intelligence testing, work on the first personality test—the Personal Data Sheet—began in 1917 and was completed the following year.

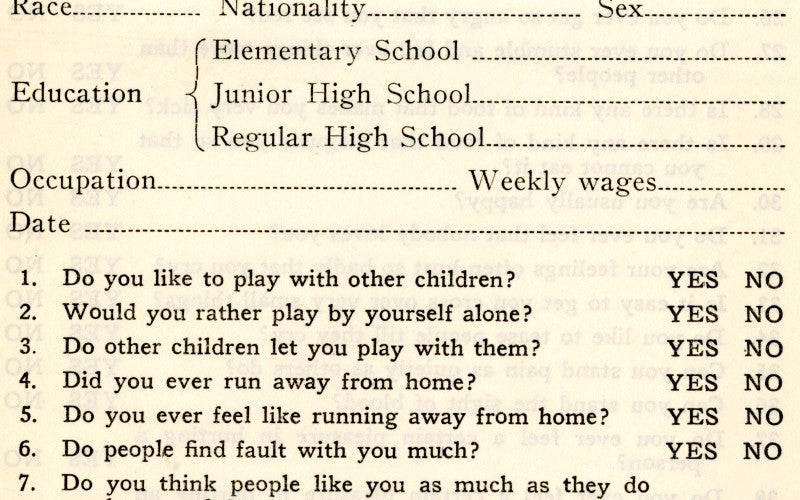

To develop the first personality test, the National Research Council assembled a Committee on Emotional Fitness for Warfare. This team examined extant accounts of mental illness to determine symptoms precipitating mental breakdowns. These were then used to generate a set of yes-or-no questions that were tested against “normal” individuals. The resulting data sheet included 116 questions, with the assumption that normal persons would on average give about ten indicating answers to these questions. One early commentator noted that “any individual who answers 20 of the questions wrongly should be suspected of instability” and “if the number of ‘wrong’ answers is greater than 30 grave suspicion of abnormality is warranted” (Franz 1920, 171).

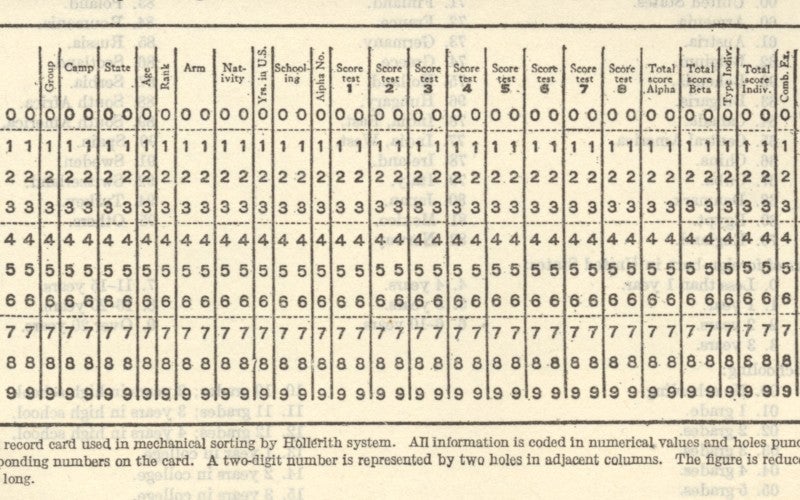

The tests were a behavioral assessment, designed to be completed by the test subject after receiving very precise instruction. They did not require a detailed interview with a psychologist nor the interpretive apparatus of depth-psychology approaches like psychoanalysis. They did not allow for special questions pertinent to any individual taking the test. The tests, rather, produced binary (yes or no, agree or disagree) or numerical (scaled) answers that could be easily normalized for computation. The test included questions such as: “Have you lost your memory for a time?” and “Are you ever bothered by the feeling that people are reading your thoughts?.” A small number of the questions were understood to be unlikely to produce false positives (see Franz 1920, 171). Exemplary questions include: “Were you considered a bad boy?” and “Do you ever feel a strong desire to go and set fire to something?” (all questions drawn from the 1924 edition of Woodworth’s Personal Data Sheet published by C.H. Stoelting Co.) With these questions, and subsequent algorithmic analysis of individuals’ answers to them, personality began to be quantified, measured, and in this and other ways subject to datafication.

The datafication of personality was quickly followed by the question of a stable standard of measure. By the 1920s there was a whole battery of psychological instruments producing traits as real correlates of measures and a scientific standard for personality psychology research.

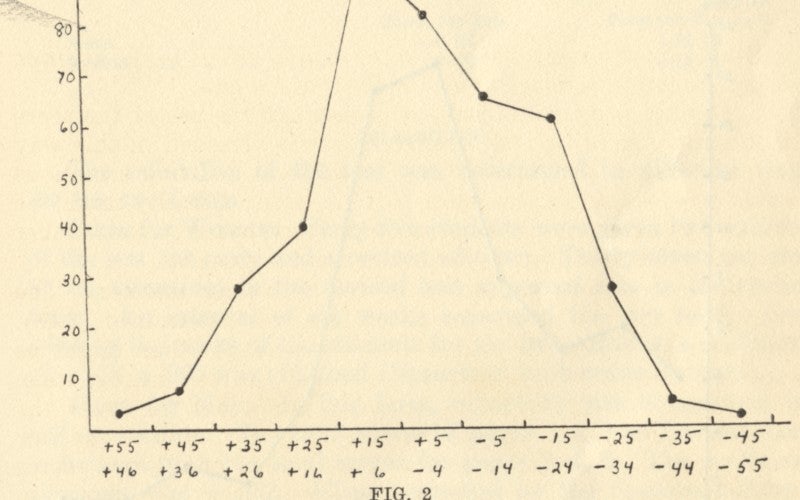

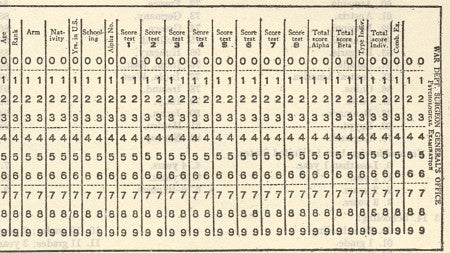

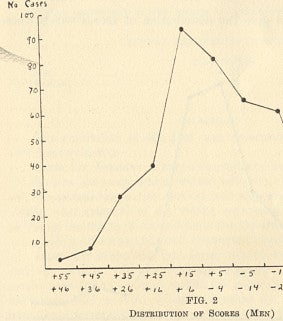

Enter Gordon Allport, who soon championed the view of the objective reality of traits on the basis of the construction of tests which could reliably measure them. In Allport’s 1928 article, “A Test for Ascendance-Submission” he sketched an account of algorithmic technologies of measurement which were tests geared toward traits (Allport 1928). He characterized trait testing technologies using numerous hand-drawn charts and a decile table on which is grouped test scores.

The article also included a sampling of the test questionnaire (consisting of verbal descriptions of situations to which the test taker responds by indicating how he or she would act), a sampling from the instructions used to administer the test, and a discussion of the process through which answers to the test questions were rated on the ascendance-submission scale and then converted into quantitative data. Regarding the status of traits in the wake of trait testing algorithms, Allport concluded traits are “a relatively homogeneous statistical phenomenon susceptible of measurement and scaling” (Allport 1928, 122).

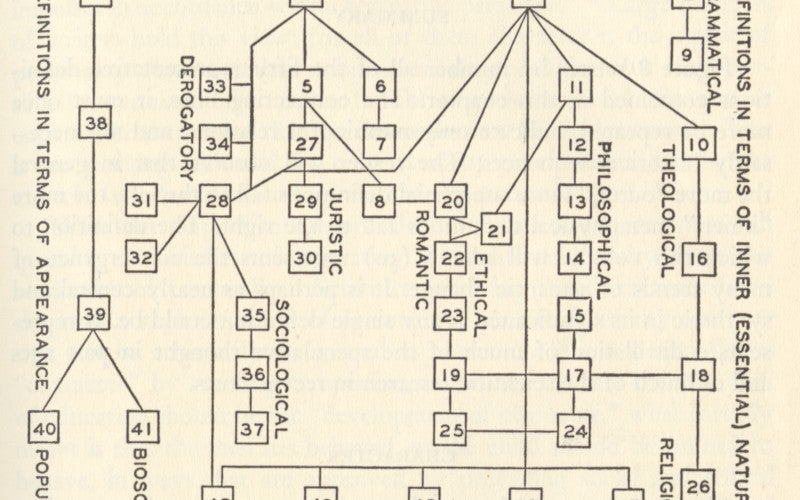

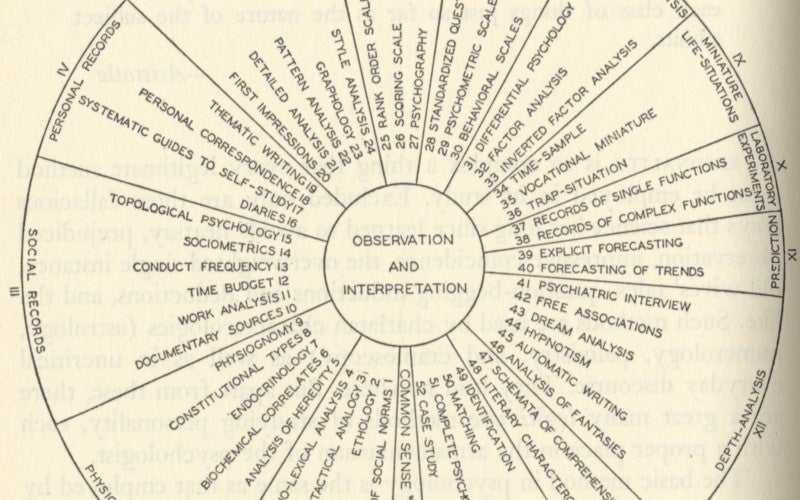

Less than a decade later Allport narrated the consolidation of traits as a stable unit of measure by personality psychology in the preface of his now-classic 1937 book Personality: A Psychological Interpretation where he boldly states “the chief novelty of my own position lies [in the concept of] traits” (1937, ix).