Genetic Information

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, when it was announced that the mapping of the human genome had been completed, it seemed for a brief moment as if we were at last on the panoramic precipice of being able to solve the wonderful riddle of the relationship between our genes and ourselves. Nearly two decades later, the biological sciences have yet to deliver their promised keys to human nature. However, rather than dissipating in disappointment, the riddle of genetic selfhood has only increased in appeal. We are now as fascinated as ever by the role genes play in the formation of who we are. Accompanying our abiding interest in our genetic human nature is a growing recognition of the increasingly complicated challenges of the political and ethical implications of the sciences and technologies of our genes. How should we analyze and assess these challenges?

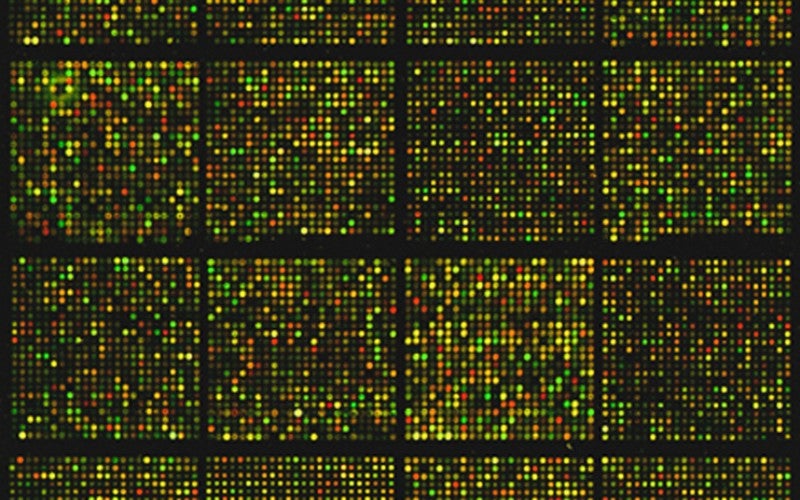

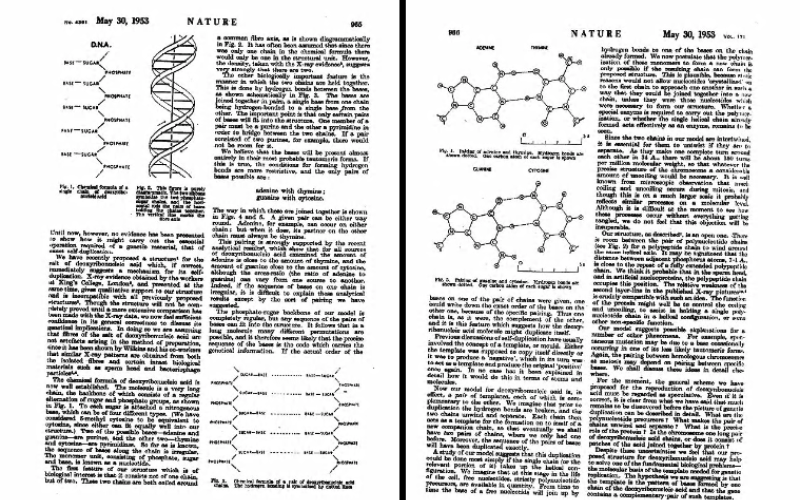

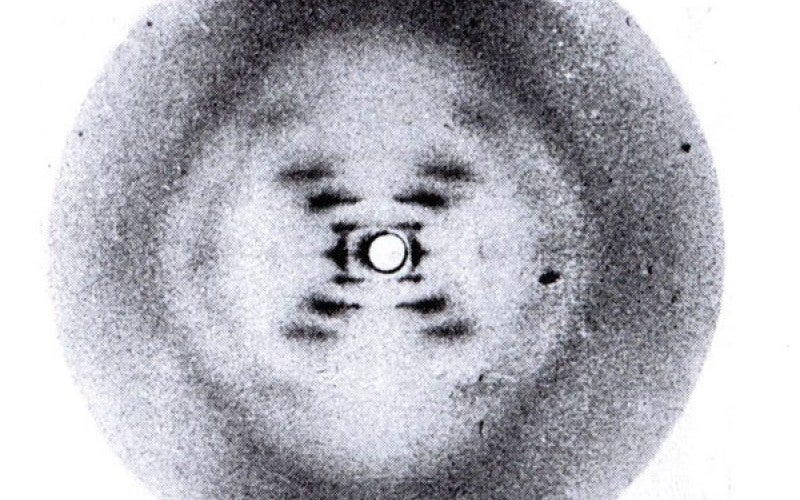

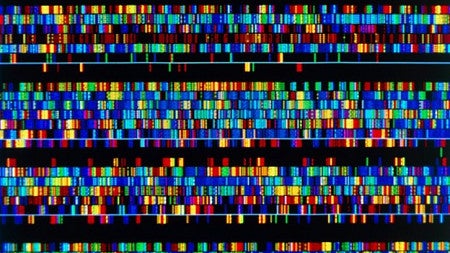

The history of the role of information systems and information theory in genetic research helps shed light on the above question. One of the most influential scientific landmarks for the crucial idea of genetic code is James Watson and Francis Crick’s development of the double helix model of DNA in 1953. It is not accidental that, in the publications in which Watson and Crick announced their discovery of DNA’s double-helical structure, they surmised that it “seems likely that the precise sequence of the bases is the code which carries the genetical information” (Watson and Crick 1980, 244). Their phrasing draws our attention to the fact that Watson and Crick could comfortably assume that the basic objects of research in genetics were processes of information transfer. In fact this was an assumption so secure that they did not even recognize a need to argue for it in their description of their research as oriented by two desiderata: “A genetic material must in some way fulfil two functions. It must duplicate itself, and it must exert a highly specific influence on the cell” (Ibid., 267). Watson and Crick could just take it for granted that “influence” was a matter of information transfer. If genetic material consisted in the specificity of sequences of bases, they could make the inference to their crucial conclusion that “the sequence is the only feature which can carry the genetical information” (Ibid.).

In Watson’s later 1968 account of the modeling of DNA’s structure, he made explicit that the functional movement at the core of genetic research, namely, from DNA to RNA to protein, was one that “did not signify chemical transformations, but instead expressed the transfer of genetic information” (Watson in 1968, republished in Watson and Crick 1980, 89). Two years later in 1970, François Jacob (winner of a 1965 Nobel Prize for his contributions to genetics) would consolidate the going view on the first page of his book The Logic of Life: “Heredity is described today in terms of information, messages and code” (Jacob 1970 [repr. 1989], 1).

What is important about such statements is that midcentury molecular biology did not position information as merely a metaphor for underlying physicochemical processes that are taken to be real. Physicochemical reality itself was conceptualized functionally as information transfers.

This information-theoretic conceptualization of genes persists in scientific research today, as is explicitly emphasized by, among others, Richard Dawkins: “The genetic code is truly digital, in exactly the same sense as computer codes. This is not some vague analogy, it is the literal truth” (Dawkins 2003, 28). Information is not a mere metaphor for genetic material—genes, genomes, and epigenetic systems are themselves informational at their core.

The genealogy of genetics culminates quite consequentially in the sequenced selfhood of “informational persons” (Koopman 2019, 1) or what Lily Kay has called “informational man” (2000, 1) and what Donna Haraway once referred to, also in relation to genetics, as a “human [that] is itself an information structure” (1997, 247). In short, if we are our genes, and our genes are data, then we are our data. If that is right, the informational persons we have become require, at least some of the time, a distinctive attention to the politics and ethics of the information that we are.

The specifically infopolitical dimensions of these sciences and technologies concern, above all, a politics of “formatting.” To understand the politics of formatting in the genetic sciences, consider a golden thread that runs through the history of these sciences from the emergent moment of molecular biology up to recent research in postgenomics. The thread is a seemingly obvious but remarkably important conceptual feature of the informational paradigm of genetics, genomics, and postgenomics: the fact that genes code for what is codable. When we take genetic materials to be essential determinants for who we are, we are taking ourselves to be programmable creatures, that is, creatures who can be formatted as codable data. Any feature of who we are that can be programmed by genes (or, in the postgenomic perspective, by complex combinations of genetic, epigenetic, and other factors) is a feature that must itself be programmable. Out of this apparent truism of genetics unfold myriad crucial implications.

In thinking through these implications, the crucial point is that whatever is formatted can always be formatted in some other way according to many alternative formats. It is in this plurality of available formats that we can and should locate the politics and ethics of our encoding. Note well that the plurality of formats is not merely a matter of a plurality of possible descriptions. A format is not a fancy: multiple descriptions and interpretations are always easy to imagine, but format multiplicity is a function of rigorous scientific work such that the point concerns the production of stable, reliable, and well-earned formats. The politics of information is a politics of plural formats, a politics of the many different available formats that data channel our lives into. The politics of formats is not to be found in an emancipatory gesture that would finally free whatever cannot be coded from reductive programming by data. The politics of formats is a function of the many ways in which data can code us: different options for coding produce different (and differently distributed) impacts and, of course, different informational selves.