Birth Certificate Standardization

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were three influential rationales for the nationwide creation and adoption of a birth-registration system. Outlined in a 1908 Census Bureau publication these reasons concerned the specific demographic, “sanitary” (or public health), and legal (or property-based) uses of birth registration. This justificatory trio had been earlier adumbrated in a series of 1903 Census pamphlets that referred back to nascent attempts to standardize birth registration across the nineteenth century. Despite there being an argumentative structure in place for decades, birth registration only began to consolidate during a two-decade period beginning around 1913. What were the early-twentieth century technologies and practices that facilitated the standardization of the birth certificate?

The emergent birth-registration system was conditioned in part by the requirements and needs of legal and public health projects. Concerning first usages of birth registration in legal contexts, Henry Bixby Hemenway, a state district health officer in Illinois, emphasized the value of standardized birth certificates in terms of the legal use of these documents for evidentiary purposes. These legal uses included “admittance to the public school,” “permission for child labor,” “establishing age,” “proof of nationality and citizenship,” “establishing the status of individuals under the provisions of the draft,” and “evidence of rights in heirship and in title to property, and in claims for pension” (Hemenway 1921, 1). The Census Bureau regarded original standard birth certificates as essential for the “protection of the rights of the individual and of the community” (1908, 7). Birth registration thus responded to needs in legal practice to verify aspects of a person's identity to secure certain rights and protections, including most emphatically property rights. Birth certificates thereby made possible new kinds of legal relations—not just new laws but new kinds of legal intervention. For instance, child labor legislation proposals could be taken seriously, and enacted, only in a legal context in which it was increasingly the case that laborers, and not just elites, could be assumed to be able to document their age (see Pearson 2015).

Yet birth registration at the turn of the century still lacked a technical apparatus for implementing the official rationales widely embraced at that point. The success of birth registration in the United States depended not only on its official trio of justifications; it also depended on a trio of emerging information technologies. These three technologies were standardized birth registration forms, a filing protocol, and an information audit.

Concerning standardized blank forms, Cressy Wilbur (chief statistician for the Census Bureau’s Vital Statistics Division from 1906 until 1914) retrospectively reported in 1916 that as late as the 1900 census, “no two states and but few cities in the country employed precisely the same forms of birth and death certificates” (1916, 23). This fact may seem innocuous, but from the perspectives of statistical demography, public health statistics, and legal records, this lack of consistency was ruinous. In the long campaign for birth registration, much attention was thus given to the design of forms and their data structures therein. Such issues can be understood through the concept of “formats” as speaking both to visual (or other sensory) design aspects and conceptual data structuring.

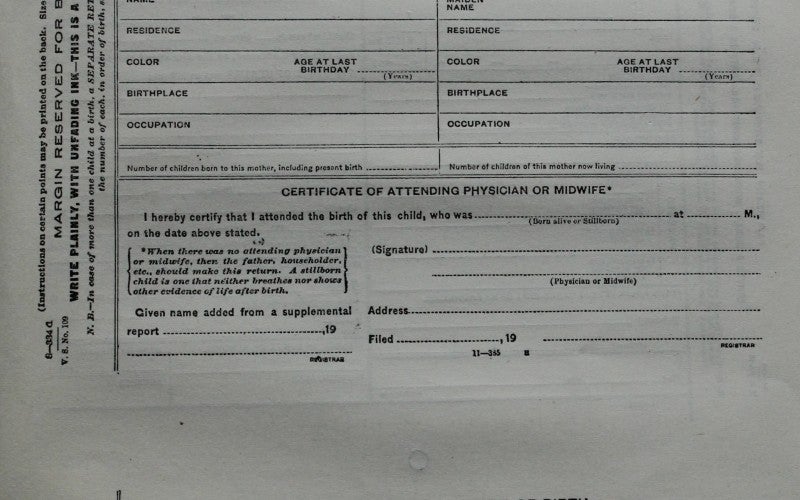

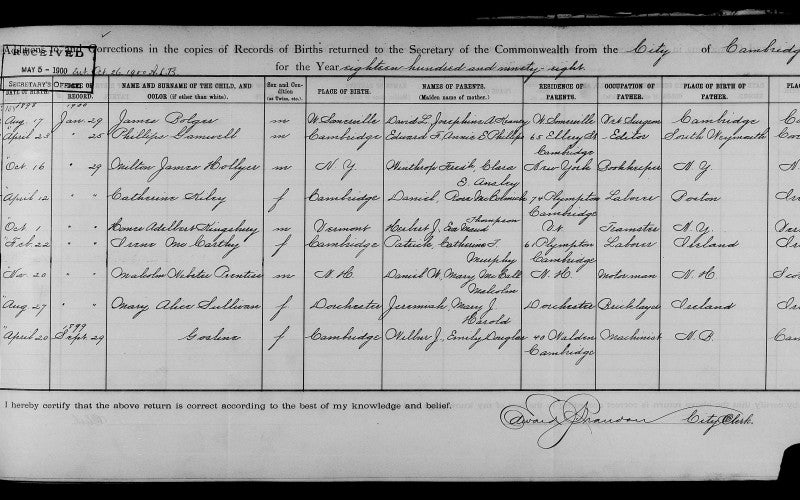

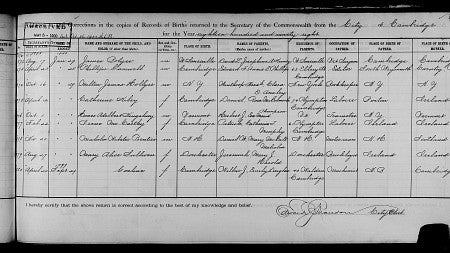

The basic framework for debates over birth certificate formatting was initialized in 1903 by the Census Bureau and the American Public Health Association (APHA) in their joint work on a standard form as conveyed in Census pamphlets, in particular pamphlet number 104, Registration of Births and Deaths. The pamphlet includes a reproduction of a standard certificate of birth designed by the APHA Committee on Demography in coordination with Census. The specifications for the form were meticulous: “Every detail called for by the standard certificate has a specific use” (1903, 28). In terms of size, the form should be “6 by 8 inches, including 1-inch margin for binding,” a shape that would “[distinguish] it immediately from the certificate of death” (1903, 27). The new certificate forms replaced older ‘book index’ systems in which various organizations (county health departments, religious institutions, and others) would enter births and other vital events into a book index (see figure at left).

The index system, though effective at mass data storage, yielded very limited search functionality. Solving the challenge of efficient data search and retrieval required not just a standardized format which afforded avoided databasing.

Enter technology two—filing protocols. Form size not only bears on capacities of data solicitation, such as that of names of different lengths—it also bears on correlative technologies of file handling and storage. After defining their size, pamphlet no. 104 suggests that the forms can be easily filed in a cabinet with drawers 8¼ inches wide by 6½ inches deep until they are ready to be bound into volumes. When ready for binding, “five hundred of these make a small and compact volume, about 2 inches thick, and 80,000 of them, when bound, require only shelf room afforded by a space of 3 by 5 feet” (1903, 30). Debates today over storage capacity are conducted in the lingua franca of “gigabytes and terabytes” rather than “inches thick,” and yet the square footage of server farms is just as important a feature of systems design today as was linear footage of shelving capacity for birth registration one hundred years ago.

Census publications detailed numerous such protocols for databasing, transmission, and reporting. At the heart of them all was a centralized administrative apparatus where every state registrar should be responsible for dividing state territory into local registration districts, appointing registrars to each district, setting a calendar for periodic reporting, and maintaining a statewide database of birth-registration certificates originated through local registrars working with physicians and midwives. Pamphlet no. 104 described the administrative apparatus as “a uniform state registration service, with a central office under a state registrar, which supplies the material, formulates rules, regulations, and instructions for carrying out the law, and receives the original certificates transmitted monthly by the local registrars” (1903, 28). But there was considerable delay in the adoption and adaption of the above model legislation by states, and the process ultimately unfolded over the long course of thirty years. The cause of delay was in the absence of a reliable way of testing completeness of registration: nobody could truly speak of the accuracy when it came to birth registration, or of success in the expansion of birth registration. All they could muster was the appearance of accuracy and success. Standard blank birth certificates in concert with a standardized filing protocol had given rise to growing masses of birth data. The key data management problem here was one of measurement and accuracy. The instrument developed in response to this problem was that of the “birth-registration test,” an early information audit technology project, following work undertaken at the Children’s Bureau beginning in 1913.

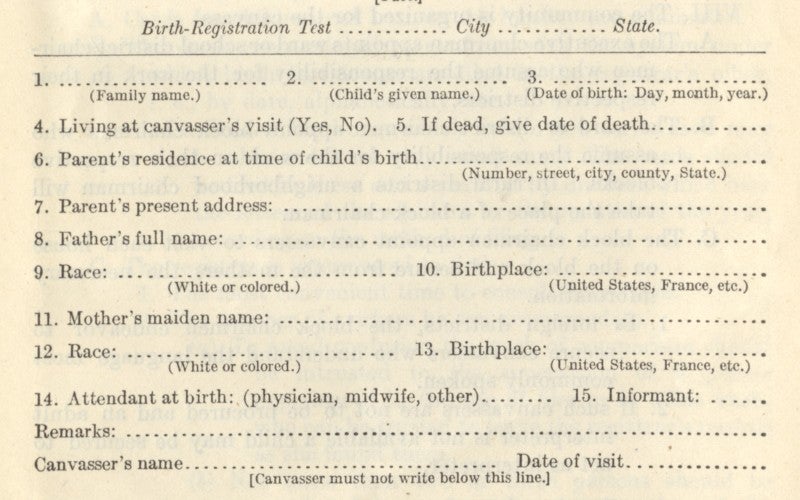

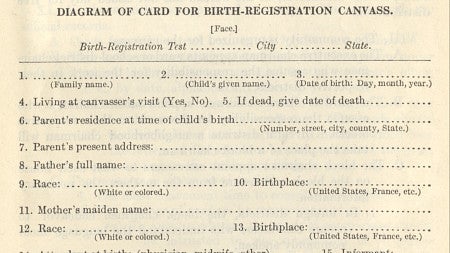

The Children’s Bureau audit of birth registration was undertaken by a force of volunteer women under the leadership and direction of Julia Lathrop (the first female head of a U.S. federal agency). The volunteer force house-to-house canvased in limited neighborhoods distributing blank forms “for a certain number of babies” in each area. These were then taken as a representative sample for a broader area. A house-to-house survey of born babies moved registration measures toward a reliable baseline against which the accuracy of haphazard registration could be checked.

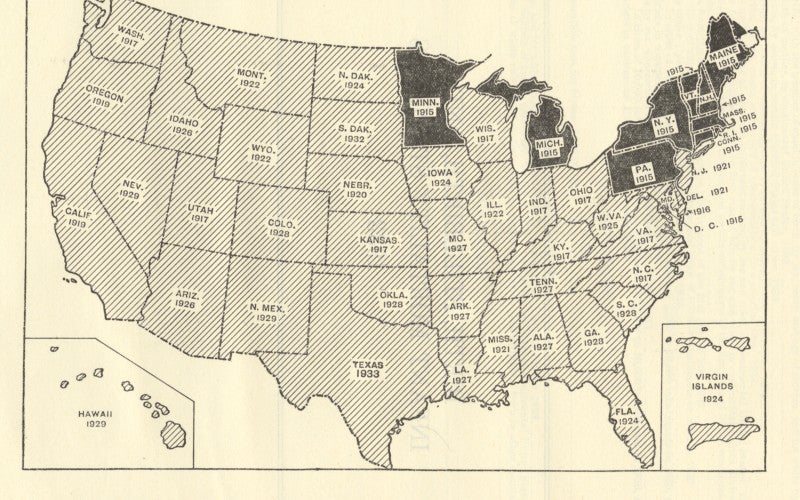

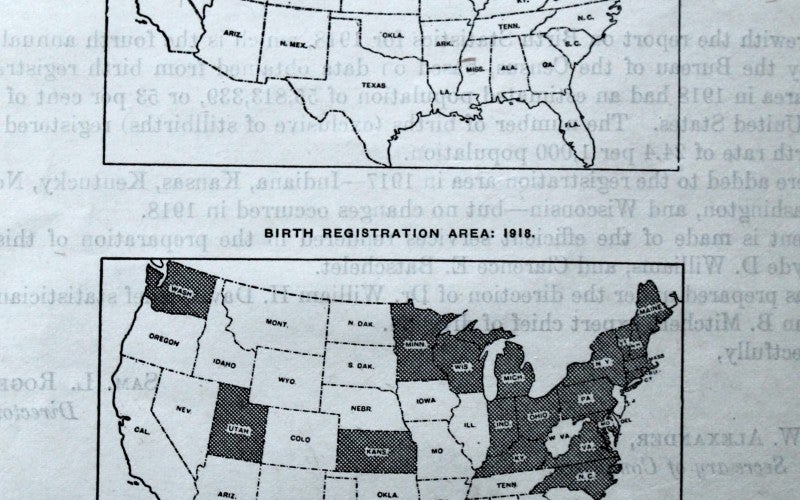

The Bureau’s decisive contributions to the informatics of birth registration ran from late 1913 to 1917. At that point, the registration test project was appropriated by the Census Bureau and subsequently referred to as the Birth Registration Area.

The Birth Registration Area was a crucial device for stabilizing the formation of an informatics of documentary identity. It defined a standard of success in birth-registration, namely the registration of 90% of newborns in a given jurisdiction (such as a state). After very halting implementation of birth-registration standards from 1903 through the mid-1910s, the target set by the Birth Registration Area was converged upon over the next few decades when in 1933 all U.S. states finally achieved 90% or higher registration. What the audit process contributed to standard forms and filing protocols was a reliable measure for the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of formats. Prior to auditing, all those data collected on the forms and stored in the files could only be a wilderness that would fail to meet the demands of a field of inquiry that, in the words of the ACHA’s director of research, “bristles with administrative problems that cry out for measurement” (Palmer 1933, 132). With a reliable measure of completeness in hand, those data could be tamed by more data, or, more specifically, metadata in the form of data metrics.

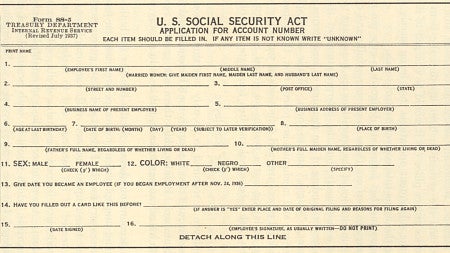

By the 1930s, the trio of technologies at the heart of birth registration (standard forms, filing protocols, and information audits) were so stable as to be readily leveraged in other projects. It took numerous agencies over 30 years (from 1903 to 1933) to achieve 90% registration of births, but just a few years later it would take only a few months (during the winter of 1936-1937) to achieve the same rate of registration of eligible U.S. workers into the Social Security system that had been established in the Spring of 1935.

Birth certificates format many of the first stable facts about us as we travel from womb to world. Yet historian Susan Pearson recently notes that “we know almost nothing about how the birth certificate became the foundational form of identification” (2015, 1146). In learning how this crucial piece of informational identification was assembled, we learn how our very selves can be taken to be stable today.