Medical Records Formalization

Medicine is often thought of as a science of the body, but it is also a science of data. In some contexts it can even be asserted that data drive health. Consider a key piece of data technology central to contemporary practices of medicine: the medical record. By situating the medical record in the perspective of its recent history, we can see how the kinds of data that are kept at sites of clinical encounter often depend on informational requirements that originate well outside of the clinic, in particular in health insurance records systems.

Health insurance records were formalized decades prior to clinical records in such a way that the former created conditions for the latter. Thus did first-generation health insurance forms institute information-gathering requirements for care providers in clinical sites. Insurance records are thus a part of the story of how it came to pass that clinical providers today would find themselves exasperated at the insurance-driven documentation requirements of their electronic medical records systems.

This relation between health insurance data and clinical health records is illuminated by understanding the broader context of medical data across the twentieth century. Historians have documented the marked lack of disease surveillance systems during the 1918 influenza epidemic followed by the takeoff of robust health informatics in the U.S. in public health in the aftermath of said pandemic (Crosby 1989 [2003], p. 204). By the 1920s, and evidently not much before then, it was both conceptually and technically possible to implement highly formalized health records systems on a mass scale. At that point, of course, much work remained for technicians to build (and then build out) such systems across multiple domains in which there were uses of health information.

This sets the stage for the formalization of, first, health insurance records (in the 1930s and 1940s) and then, second, clinical medical settings (in the 1950s and 1960s).

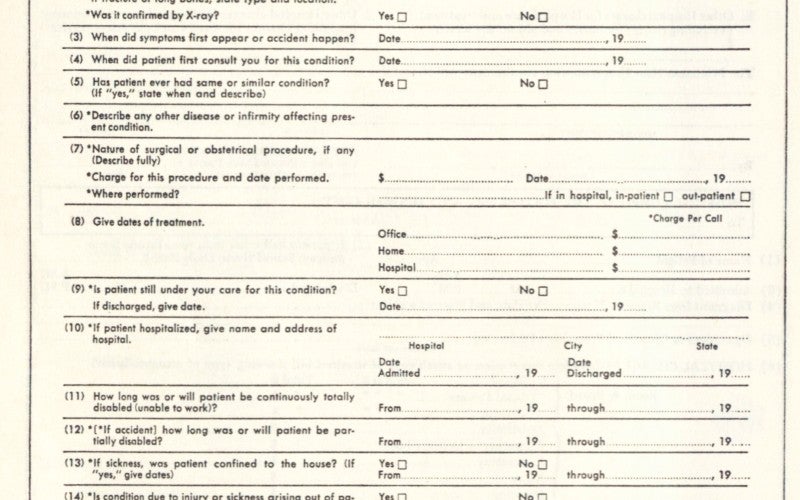

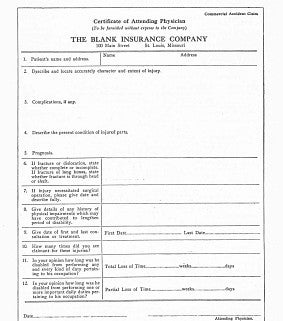

Health insurance began to boom in the U.S. in the 1930s and 1940s. An important part of this boom was the formalization of a modern health insurance information system. This system includes at least two kinds of formalized data. First, there are populations-level statistics that feed into actuarial estimates to calculate costs, premiums, and other incomes. Second, there are individual-level records about insured customers, some of which are standard blank forms supplied to (and filled out by) the insured, others which are standard blanks supplied to billing departments and physicians (or their assistants) at sites where health care is provided. It is the latter that is the authors’ primary interest.

The individualized documents developed by health insurers in this period included both records application forms for prospective customers or purchasers of insurance and physician-facing forms that any medical facility caring for an insured patient would need to fill out. As these latter forms eventually came to accompany more and more patients, hospital personnel from administrators to doctors and nurses would adjust clinical care protocols (as well as informal office practices) to keep up with this information technology that was increasingly an essential part of any clinical interaction.

To see how these self-adjustments came to seem necessary, consider the long history within which insurer records systems have been delivered to the site of clinical care with the clear expectation that their formats and protocols will be abided. These expectations were from early on backed not just by individual insurance companies, but also by the heft of insurance industry professional organizations. In an early study of health insurance in 1942, C.A. Kulp observed that industry professionalization beginning in the 1930s was characterized by more objective and uniform standards for rate-making as well as more uniform policy contracts (Kulp 1942, p. 376). These tendencies toward formalization were implemented through standard forms first developed by professional organizations and then promulgated through such of their professionalizing publications as textbooks.

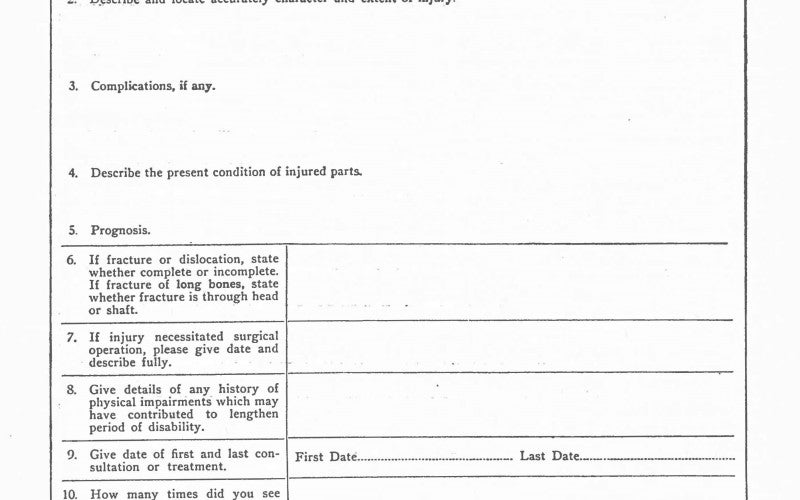

Consider an example standard form featured in Appendix VI-D of Edwin Faulkner’s educational 1940 textbook Accident-and-Health Insurance (Faulkner 1940) published in the McGraw-Hill Insurance Series. The narrow specificity of the form’s intended use is of interest. Also notable about this document is simply the way it indexes the need for a physician attending to a patient to produce a series of medical observations that have been pre-formatted by an insurance company. The specimen form asserts itself only modestly. Yet it is remarkable in what it demands. It is a record produced by an insurance form for commercial purposes which requires of a licensed clinical practitioner that they specify certain medical facts, and conduct an examination for their discovery, whether the doctor themselves finds these particular facts relevant. The insurance form does not just ask for data, but rather it explicitly and precisely demands the provision of certain medical information.

Whenever such a form would appear in a clinical setting where patient records remained relatively informal or idiosyncratic, they would bring with them powerful incentives toward adjusting clinical practices toward the more efficient provision of the requested medical information.

Most historians of the field hold that medical informatics proper takes off beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Collen 1995, p. 37). This is when the wide-scale usage of formalized records in clinical settings began.

This suggests that the formalization of clinical medical records came well after the formalization of medical information for health insurance purposes. When the two medical information systems of clinical records and insurance files met in a heady moment of culture-wide computerization in the 1960s, the computational systems that came first instituted tendencies and dependencies that later technicians often needed to respect. In short, medical data was constrained by path dependencies.

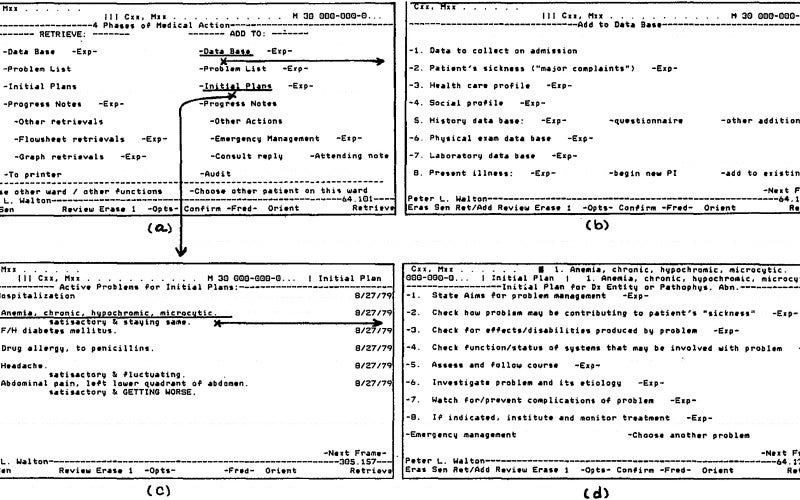

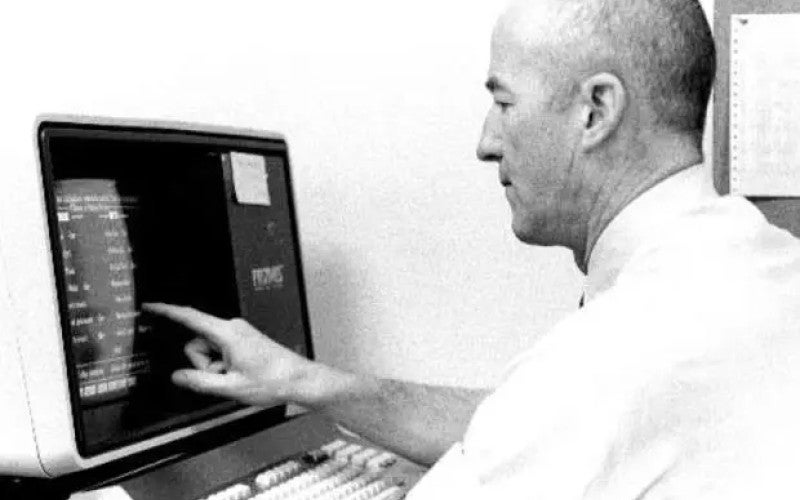

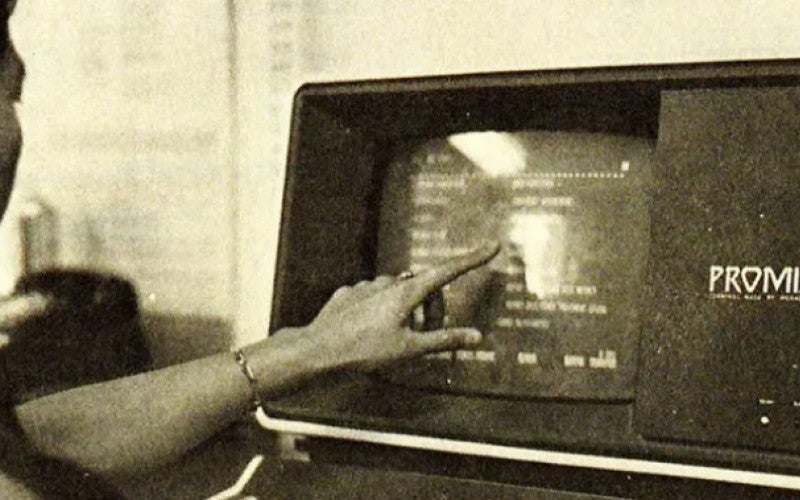

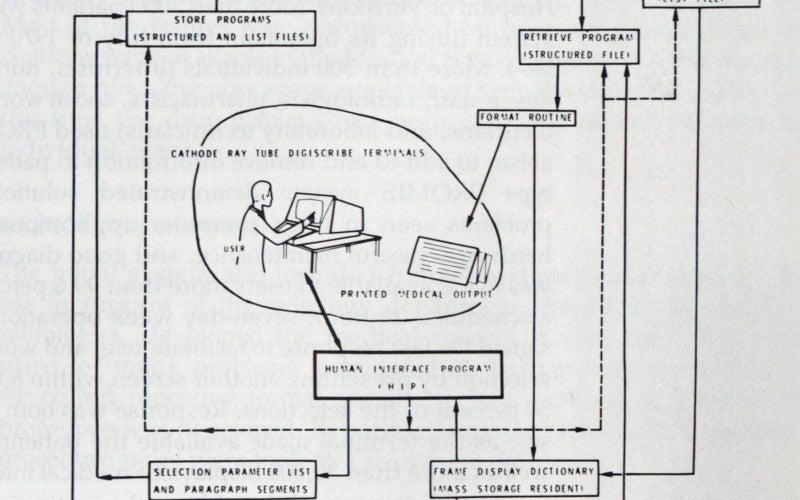

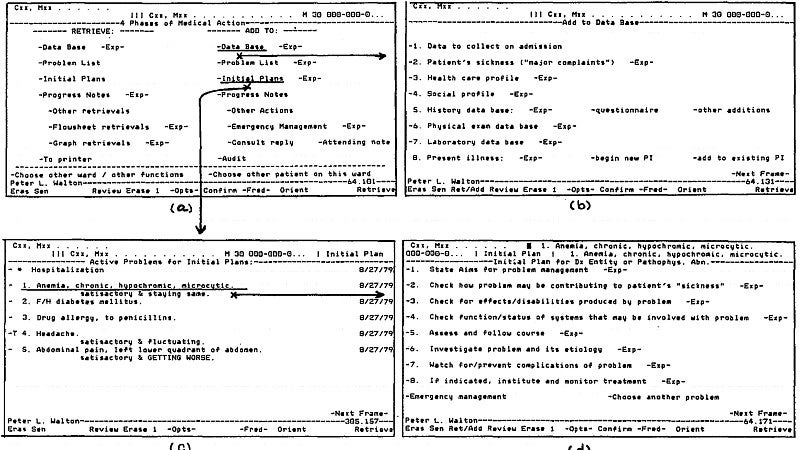

Among the first designers of computerized clinical medical informatics systems in the 1960s was Lawrence Weed, who designed multiple systems including the PROMIS system (named after Weed’s ‘Problem Oriented Medical Record’ data structure). Weed and his team, as well as the clinicians they consulted for, would have had to deal with the fact that insurance records systems dating back to the 1940s were already circulating in many clinical settings undergoing computerization. The relatively informal clinical recordkeeping apparatus that new computerized systems sought to formalize in the 1960s had in fact already been subject to at least some formalizing requirements due to the presence of insurance records in the clinic going back to the 1940s.

If it is widely understood that health insurance organizations play an outsize role in health care in the U.S. today, there is a technological dimension to this influence in addition to its widely-acknowledged economic explanations. Yet for all the debates that rage about health care, and all the explanations that aim to account for policy divides, too little attention is paid to the mundane data systems at the heart of contemporary medicine.Health is beset by a technological inertia that conditions medicine across its many iterations. This is just one of the many ways in which data drive health, but surely also disease.